Right to Repair and Sustainability A Viable Concept in Modern Product Systems

Have you ever thought about how product repairing might help you? And why can this not be done for most of the products? Would this give you the whole rights to your product? Considering the Circular Economy and Product Design, we would like to strengthen the idea of Product Repairing and its connection with sustainability. After the end of a product’s life, which the consumer usually declares in most cases, a product has to be reusable by repair, dismountable, and its parts recyclable to a high percentage. Most of the products with specific functionalities cannot be repaired by the users, which would be a great option regarding product sustainability.

The Right to Repair (R2R) as a concept and real-life practicability has become central to sustainability discussions, offering potential to reduce e-waste, extend product lifespans, and decouple growth from resource depletion. Despite increasing legislative attention and public interest, practical barriers remain deeply embedded in product design, business models, regulatory frameworks, and consumer behavior.

Strategies to reduce material throughput and environmental externalities, considering sustainability approaches and focus, are gaining urgency. Among these, the Right to Repair is a relatively low-cost, high-impact intervention. By enabling users and independent technicians to maintain and extend the life of products, repairability reduces the need for raw material extraction, lowers carbon emissions from manufacturing, and minimizes electronic and household waste. Theoretically, this aligns closely with circular economy principles and supports environmental and economic resilience.

However, implementing R2R is not straightforward. Across sectors—from electronics to agriculture—products are often difficult to repair, not necessarily due to intent but because of how they are designed, built, sold, and regulated. We want to explain why repairability remains a challenge and how its absence undermines sustainability goals, even in markets and regions where R2R is legally supported. We would underline key factors that impact the R2R options.

F1 – Design Constraints and Material Sustainability

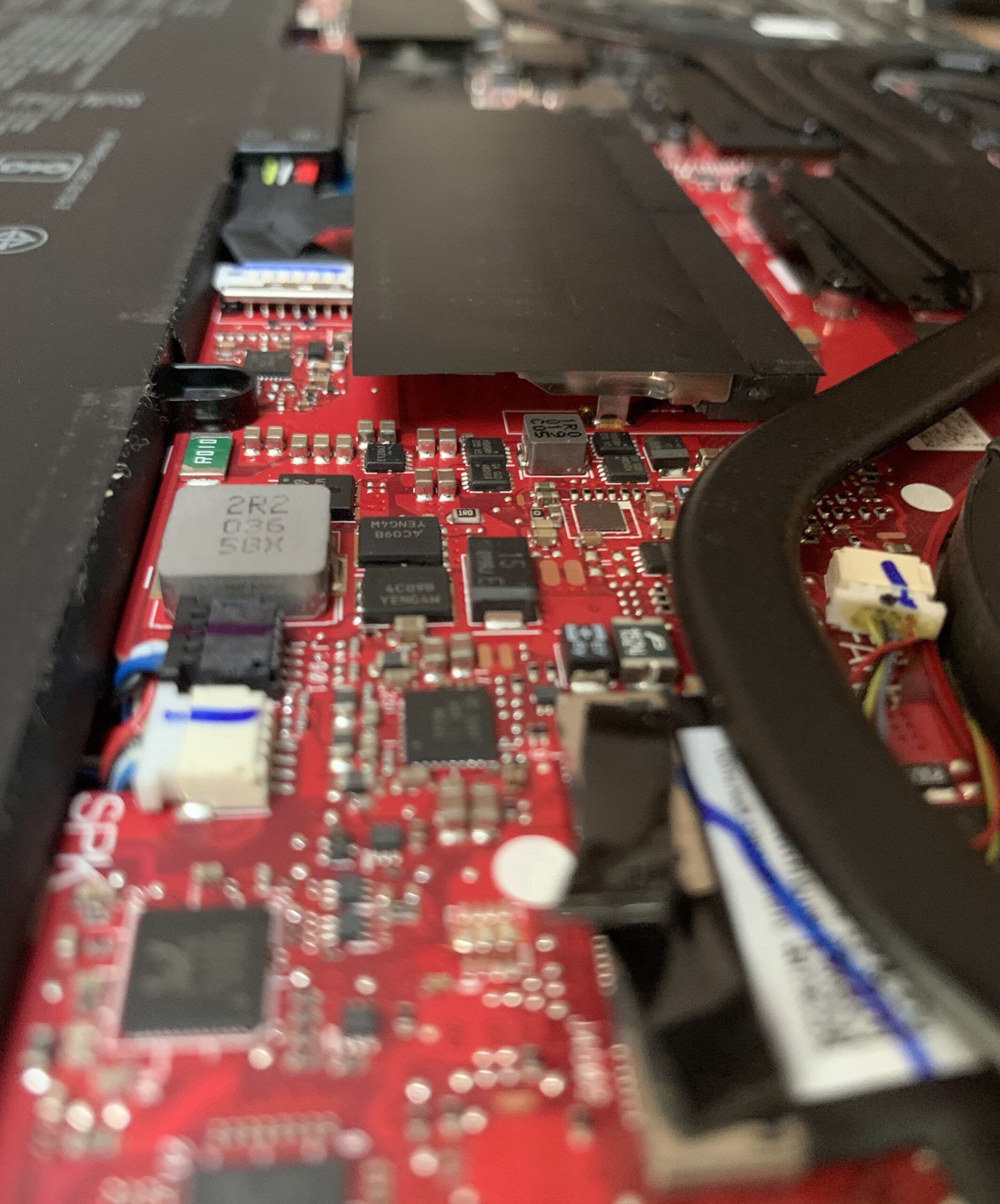

Product design plays a foundational role in determining whether items can be repaired or must be discarded. Many modern devices prioritize compactness, weight reduction, and sleek aesthetic appeal—factors that are valued in both consumer markets and logistics chains. However, these same features can make repair more difficult. Integrated components, glued enclosures, and non-modular architectures complicate disassembly and replacement, increasing the likelihood that products are discarded prematurely as Graziano & Trotta revealed in 2020.

These aspects have material consequences. According to the Global E-waste Monitor (2024), only 22% of global electronic waste is properly collected and recycled, while the rest often ends up in landfills or is processed informally, releasing toxic substances and wasting valuable metals such as gold, cobalt, and rare earth elements. Designing products to be repairable and upgradable could reduce this burden, supporting more sustainable material cycles and lowering the environmental impact of resource extraction and manufacturing.

Some manufacturers have begun to address these issues through modularity and replaceable components—examples include products like the Fairphone or Framework laptop, which are designed with ease of disassembly and part replacement in mind. Yet such models remain niche. Wider adoption is constrained by engineering trade-offs, cost pressures, and legacy supply chain systems optimized for non-repairable devices.

F2 – Business Models and Lifecycle Economics

Traditional product-oriented business models prioritize unit sales and margin optimization, often creating disincentives for repair. For example, if a product is sold at a thin profit margin, extended lifespan through repair may reduce future sales without increasing short-term revenue. In contrast, business models oriented around planned replacement—often called “planned obsolescence”—may encourage faster turnover, which can increase material waste and energy consumption.

That said, newer circular business models—such as PSS – product-as-a-service or SM – subscription models—are beginning to shift incentives. In such systems, companies retain ownership of products and are thus motivated to design for longevity, repairability, and reuse. Pilot programs in sectors like commercial appliances, industrial equipment, and office electronics suggest that such models can support profitability and sustainability, although scaling them to consumer markets remains complex.

“If you can’t fix it, you don’t own it.” — Kyle Wiens, CEO and co-founder of iFixit

F3 – Regulatory and Legal Complexities

Legal frameworks significantly influence access to repair. Intellectual property law, safety regulations, and software licensing all play roles in determining whether consumers or third parties can legally and practically repair products. Efforts to address this have gained traction. The European Union introduced Ecodesign regulations requiring that certain appliances (e.g., washing machines, refrigerators) be repairable using commonly available tools, with spare parts available for at least 7–10 years post-sale (European Commission, 2021). In the U.S., several states have passed or proposed R2R laws mandating parts and manuals be made available to consumers and independent repair providers.

However, implementation is uneven. Many current laws focus on specific product categories, exclude software-controlled functions, or lack enforcement mechanisms. Furthermore, regulatory uncertainty can deter companies from investing in redesigns or publishing repair documentation across product lines.

F4 – Cultural Factors and Repair Literacy

Sustainability is not only technical or legal—it is also cultural. Repair was once a household norm, especially in lower-income settings where resourcefulness was essential. But in many industrialized economies, repair skills have declined, and the social value of maintenance has eroded. Educational systems often exclude basic technical literacy, while media and marketing emphasize novelty and replacement over care and longevity.

Rebuilding a culture of repair through public education, community repair events, and maker spaces can support sustainable consumption patterns. Initiatives like Repair Cafés and iFixit have demonstrated growing interest, but they remain grassroots and localized. Without institutional support, their systemic impact is limited.

F5 – Sustainability Implications and Systems Thinking

Repairability is deeply connected to sustainability across multiple dimensions. Environmentally, it reduces the need for raw material extraction and cuts emissions from manufacturing and logistics. Economically, it creates opportunities for localized labor and reduces total cost of ownership. Socially, it fosters autonomy and resilience, especially in underserved communities where replacement may be unaffordable.

However, enabling repairability requires coordination across product design, business strategy, legal frameworks, and cultural practices. It is a systems-level challenge. Policies that address only one dimension—for instance, requiring spare parts but not tool access or software unlocks—are unlikely to achieve meaningful outcomes. Holistic policy frameworks, including international standards on repair scoring, product passports, and extended producer responsibility (EPR), are essential to make repair central to sustainable product lifecycles.

Repair is not a technical inconvenience; it is imperative for sustainability. Enabling this requires overcoming structural barriers in how products are designed, regulated, marketed, and used. While no single actor can shift the system alone, coordinated interventions by policymakers, manufacturers, educators, and civil society can gradually restore repair as a viable and mainstream option.

The Right to Repair is thus not only about consumer rights or cost-saving—it is about redefining our relationship to the material world. In a climate-constrained, resource-limited future, repair will be essential. The question is not whether we can afford to make products repairable, but whether we can afford not to.