The robotization of our lives: what the figures show, what we gain, what we risk, and how to do it right

Robotics has expanded beyond factories and entered homes, warehouses, fields, and hospitals. The change is evident in the figures: the global density of robots in factories reached 162 units per 10,000 employees in 2023, more than double the number from a few years ago. South Korea remains the world leader, with 1,012 robots per 10,000 employees, while China has risen aggressively and overtaken Germany, reaching approximately 470 robots per 10,000 employees, a sign that automation is becoming a central economic issue, not a passing fad. These data come from the annual reports of the International Federation of Robotics and market analyses for the years 2023–2024.

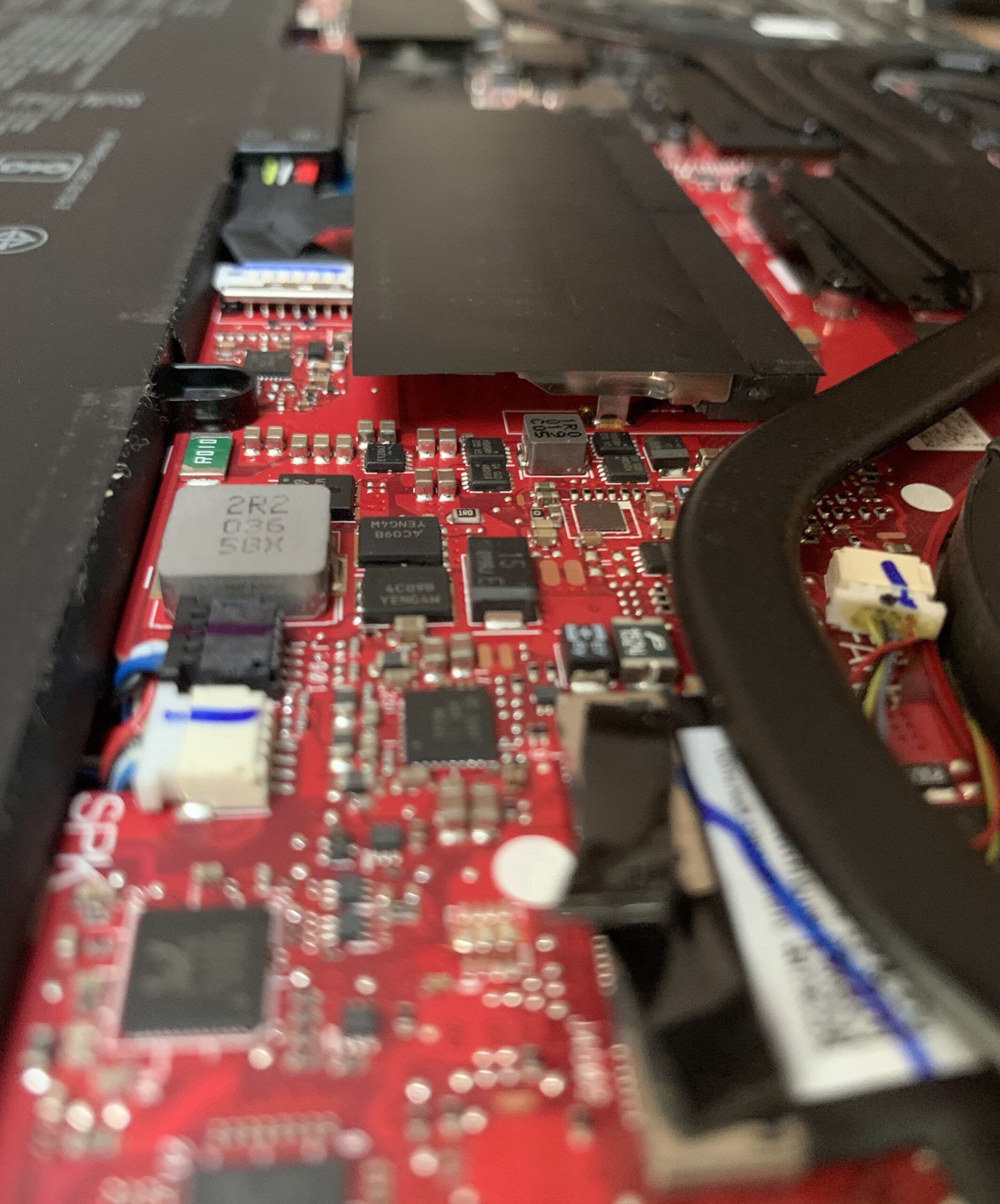

At the same time, another statistic tempers the enthusiasm: in 2022, the planet generated around 62 million tons of electronic waste, and the documented collection and recycling rate was only 22.3%. The current trend indicates that, without policy and design changes, the rate could drop to 20% by 2030, while the total volume of electrical and electronic waste is expected to continue growing. This means that any new wave of smart devices, domestic robots, or industrial equipment that is poorly designed in terms of life cycle and reparability will amplify the problem. These conclusions are supported by the “Global E-waste Monitor 2024,” coordinated by ITU and UN partners.

Among other things, robotization primarily means two things: time saved and exposure to data collected in private. Autonomous vacuum cleaners and mops, lawn mowing robots, smart ovens, and refrigerators can actually give you back hours or help you balance your personal time, and assisted cooking can reduce food waste through controlled dosing and temperature settings. However, most of these products rely on permanent connectivity and software updates, and many utilize batteries and key components that, although not easily replaceable, often prompt users to discard the device at the first sign of a serious defect. In other words, the convenience benefit can become an environmental cost if there is no repairability and an honest long-term parts policy.

So, what can you do in your daily life to strike the perfect balance between necessity and the social or environmental impact it creates? The practical conclusion is straightforward: choose products that can also function offline, verify that parts and service are available for at least 7–10 years, and monitor what data leaves your home. We need to understand the context of e-waste and think about our moral obligation not to be tempted by “fads” but rather to think proactively about how we can contribute.

In warehouses, retail, and logistics, mobile robots and collaborative arms enhance productivity and reduce the risk of accidents in repetitive operations. In agriculture, vision-assisted harvesting and targeted application of fertilizers and pesticides minimize resource consumption and soil impact. In manufacturing, automated visual inspection reduces scrap and stabilizes quality. All of these are compelling reasons why robot density is increasing year after year in economies that rely on exports and competitiveness.

“The pace of automation is accelerating, but our ability to adapt our skills and policies often lags behind.”

— Erik Brynjolfsson, Director of the Digital Economy Lab at Stanford University (2023)

What is the social impact of robotization?

We utilize robots and digital technologies to streamline processes, increase productivity, and reduce waste; however, do we think strategically about how this can have an adverse domino effect that we cannot accurately anticipate? Yes, technical advantages come with a social cost, but what is that cost? Some entry-level jobs are being replaced or shifted to supervisory, maintenance, and digital orchestration roles. OECD analyses show that, on average, approximately 27–28% of jobs in developed countries are at high risk of automation. This does not mean “inevitable mass unemployment,” but rather that the transition must be paid for and organized, including retraining, enhancing basic digital skills, and reallocating people to value-added tasks.

Europe has begun to correct the flawed market design with two essential instruments.

- The first is the Directive on the “Right to Repair,” adopted in 2024, which extends the legal warranty by 12 months when the consumer chooses repair over replacement and requires better access to parts and service information. It is a mechanism that encourages manufacturers to design durable and repairable appliances, ensuring that consumers are not penalized for making responsible choices.

- The second is the European framework for artificial intelligence (AI Act), which treats applications differently depending on risk and imposes stricter requirements where systems can directly affect people’s safety, rights, or opportunities. In practice, this means that robots integrated into critical processes must comply with more stringent rules on transparency, safety, and data governance than household gadgets.

Is robotization sustainable? A particularly sensitive question

The central question is whether the robotization we are adopting is sustainable or merely short-term profit with hidden costs for people and nature. The answer lies in a few verifiable criteria.

Sustainable robotization has a life cycle analysis that shows a net benefit:

- Energy, material, and waste savings during use exceed the footprint of manufacturing, operation, and end of life.

- It has real repairability: screws instead of adhesives, accessible service manuals, parts available for years, replaceable batteries, and a collection or buy-back program at the end of the product’s life.

- Processes the minimum necessary data, prefers local (edge) inference, and gives the user precise control over the camera, microphone, and logs.

- On the other hand, “greedy” robotization is easy to recognize: products that are difficult or impossible to repair, closed ecosystems that block independent service, massive data collection without justification, and outsourcing of waste and retraining costs to communities.

Measures that we can implement to reduce the negative impacts of robotization

What can we do, specifically, to ensure that the decision is sound and easy for everyone to understand? In the household, we choose products that work without the cloud for basic functions. We look for energy labels and firm promises of parts and service, and we utilize the new European rules to request repairs and extended warranties when necessary.

In companies, you don’t jump straight into “automation everywhere,” but start with a well-defined pilot on a single task, measured thoroughly over three months on four lines: people (safety and satisfaction), planet (consumption and waste), profit (cost per unit and quality), and data (zero incidents, short retention). Scaling up only occurs if all indicators show progress. At the same time, part of the productivity gains must be allocated for retraining the affected personnel; otherwise, in the medium term, the technical gains will translate into social losses.

If we want to draw a direct conclusion, robotization can free up time, create safer jobs, and produce better products. In agriculture, it can also reduce water and chemical consumption. Just as easily, poorly designed robotization can inflate mountains of e-waste, normalize invasive surveillance, and drive down wages for those just starting.

The difference between “progress” and “derailment” is not made by the technology itself, but by how we choose, regulate, and pay for the transition. Data on the growing density of robots, the risk of job automation, and the e-waste crisis are not theoretical warnings, but benchmarks for smart decisions: repairability over replacement, limited data instead of unlimited collection, measured piloting before scaling, and the use of European legal instruments to put pressure on the correct design of products.

This is how you achieve robotization that works for people and nature, not against them.